Consider This Your Annual Reminder to Read On Fairy Stories

because yes i will share this post every mid-september

Hello, and welcome to Under the Pine Tree! My name is Jess. I’m a Catholic wife and mother in my late twenties currently in the process of writing the second draft of my first book of a series of fantasy novels ever so dear to my heart that I hope you will be able to enjoy someday. Until that day comes, however, here on Substack, I primarily document the ups and downs of that journey, hopefully offering encouragement and in-the-trenches kinds of advice to anyone out there who may benefit from it it. Especially if they’re crazy enough to attempt writing novels with a young child in the house like me. Thanks for stopping by, subscribe if you like this post, and God bless you now and always!

It’s Hobbit Day!

(almost)

Now. I was originally going to do this next week, when we’re actually closer to the great day of September 22. However, I’ve been a bit slammed trying to keep up with novel writing and mothering and life recently — all good things, nothing to worry about — so I’ve decided to move it up by one week to give me a touch more time to work on my next new post.

But even when I made this post last year, I genuinely had the intentions of re-posting it every mid-September. Tolkien’s On Fairy Stories is foundational in my understanding of faith and creativity, and I hope it can do something powerful for you too.

Enjoy!

(Even if we’re a week early — hey, it’ll just let you be done with it by the time Hobbit Day arrives, nothing wrong with that!)

It’s (almost) September 22!

That means it’s (almost) Hobbit Day!

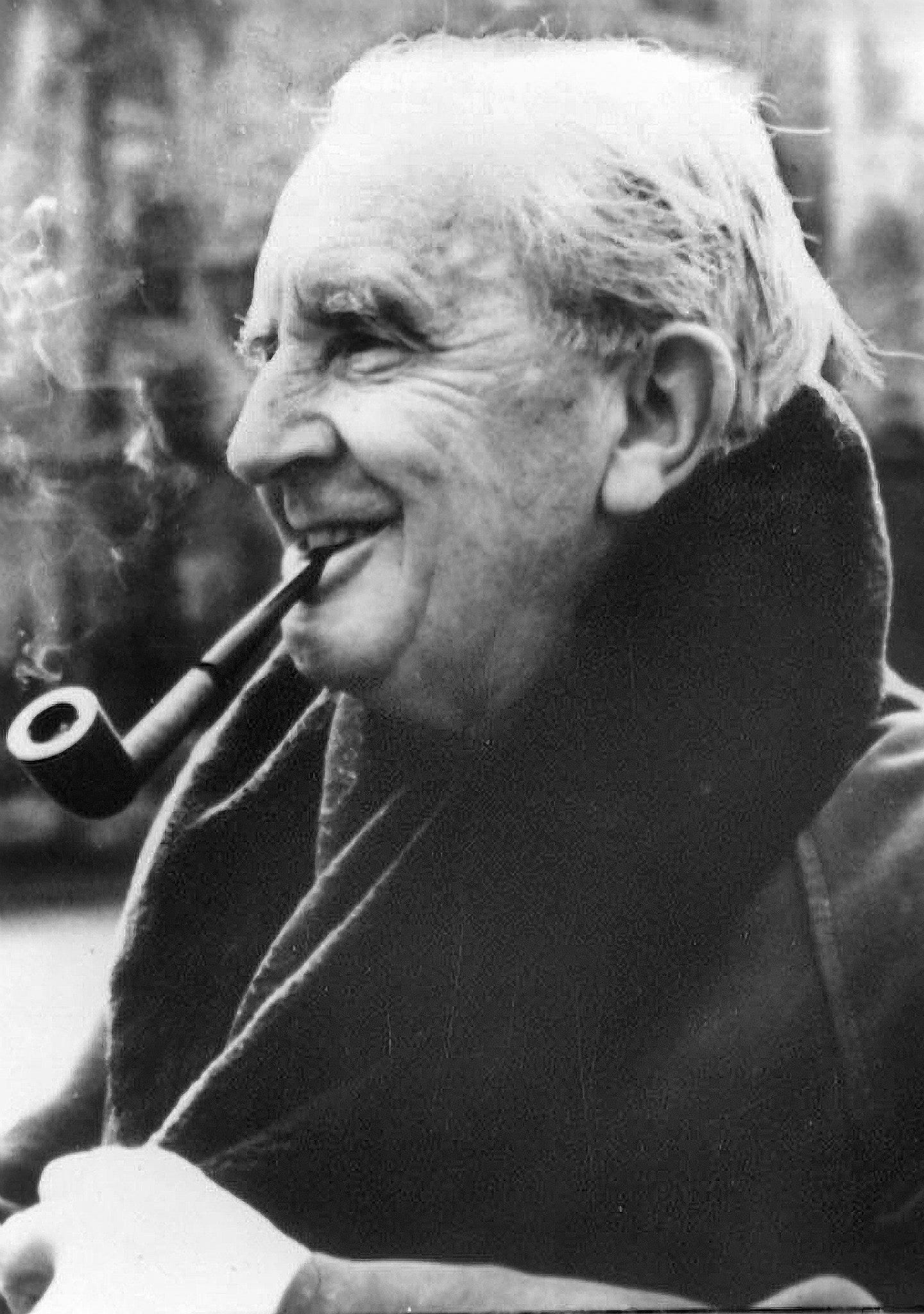

The birthday of both Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, September 22 was declared to be Hobbit Day by the American Tolkien Society in 1978, and so naturally today is a most appropriate day to think about anything and everything related to the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

Now, I’m far from alone in this sentiment, but I like Tolkien a lot. A lot a lot.

I think The Lord of the Rings is great. I read it for the first time my freshman year in high school and several times since then. The Hobbit I had actually read in middle school, but it was ultimately Frodo’s story that made me truly fall in love with Middle-Earth and lead me to love Bilbo’s more. I tackled and enjoyed The Silmarillion too, along with some other Middle-Earth tales and plenty of Tolkien’s letters and essays, my favorite of which (that we’ll be discussing a good amount today) being On Fairy Stories.

Of course, to celebrate Hobbit Day I could spend some time talking about characters, ideas, and plot points from the stories themselves, but I’d like to take a bit of a more personal approach today.

Because few writers out there have had such a long-standing and profound influence on my life as J.R.R. Tolkien. It would not be an exaggeration to say that I don’t know if I would be writing today if it were not for him. This isn’t a claim entirely exclusive to Tolkien, as it was the back-to-back-to-back experience of Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, and Star Wars between late 2010 and early 2012 that ultimately lead me to the conclusion that I wanted to write a fantasy novel. I’ve also had plenty of wonderful influences since then ranging from Dostoevsky to an immense assortment of anime. (Never let it be said that I lack a range of storytelling interests.)

But there is something very special about Tolkien for me.

Of course I love the stories themselves. I cry at any number of scenes between Frodo and Sam no matter how many times I read or watch them. A map of Middle-Earth sits above my television and my bookshelves are decorated not just with Tolkien’s books but a variety of other hobbity things. For several years it was a New Years tradition for my siblings and I to watch all three extended edition films starting at the crack of dawn and sometimes going beyond midnight depending on how many breaks we took during the day. I’m practically counting down until the day I can read Tolkien’s work with my son and any other children we may have in the future. They’re just incredible, moving stories that have few equals.

But there are a lot of stories out there that I love. What makes Tolkien special for me are not purely his stories in themselves but the way he thinks about stories in a larger, wider sense.

I mentioned On Fairy Stories earlier, but quite frankly, I don’t think there is any essay out there that has been quite as influential in my life as this one. It’s not something that I would really consider to be “lesser known” or anything like that, as it probably is among the most famous of Tolkien’s essays, but his essays are definitely less widely read than his novels. As such, while there’s a good chance you, dear reader, have heard of On Fairy Stories, perhaps you haven’t read it in full.

Today, I bid you… read it.

Or, if you have read it… reread it.

It’s honestly a magnificent essay. I’ve read it many times and each time I read it I find more gems within it. As a writer, as a Catholic, a human being, I love it.

It captures more eloquently than anything I’ve ever read why I want to write, and honestly why I like to read as well, but we’re focusing on writing today.

Because the desire to write stories is a weird thing. A lot of the time when you ask writers why they write, they answer something along the lines of… I have to, I don’t really know why, but I kind of just want this more than most other things in life. There’s this story (or many stories) that I want to tell and I don’t know what I would do if I didn’t.

These aren’t bad reasons, but they are very nebulous. They certainly resound as true in the ears of fellow writers, but I honestly have no idea how they sound to anyone else. Though I will say, I do have my pet idea that everyone does have a story they want to tell, they just try to tell it in ways other than formal writing. But that’s a thought for another time.

In any case, what makes Tolkien and On Fairy Stories special to me are his ideas that connect storytelling to our deepest humanity. How could I not be struck to the heart when I read things like this?

“Fantasy remains a human right: we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.”

Perhaps, dear reader, you too are Christian, or perhaps you are not.

I am, however, and Tolkien is too… but this connection he makes between human storytelling, particularly fantasy storytelling in its “sub-creation” of a “secondary world,” and being made in the image and likeness of a Creator God… well, it’s quite frankly life-changing. One of those things that invites you to view your day-to-day life as a creation of a work of art and bids you to never forget to offer up what you create to Him who made you.

I strive to create, we all strive to create, because He does.

It’s baked into our very humanity, and looking at one’s life and one’s work through this kind of lens honestly enchants the entire thing. It’s stunning to reflect upon.

And yeah, it’s why I write.

At the end of the day, Tolkien says it all better than I ever could, so as I said earlier, really… just read it for yourself. Read it in full.

I’ve linked the essay here.

Or, if it’s more your style, you can listen to an unabridged reading of it here:

I’m going to include a large chunk of the ending of it here, however, so if you read nothing else, please do read this. It is a rather long essay at the end of the day. Rather academic as well, but take your time. Work through it bit by bit, I don’t think you’ll regret it.

There’s talk of what makes a fairy story a fairy story, the magic of language, the relationship between myth and reality, the validity of escapism, the importance of joy and subverted disaster, or eucatastrophe, among plenty of other things…

But here’s my favorite part (emphasis mine)…

This ”joy” which I have selected as the mark of the true fairy-story (or romance), or as the seal upon it, merits more consideration.

Probably every writer making a secondary world, a fantasy, every sub-creator, wishes in some measure to be a real maker, or hopes that he is drawing on reality: hopes that the peculiar quality of this secondary world (if not all the details) are derived from Reality, or are flowing into it. If he indeed achieves a quality that can fairly be described by the dictionary definition: “inner consistency of reality,” it is difficult to conceive how this can be, if the work does not in some way partake of reality. The peculiar quality of the “joy” in successful Fantasy can thus be explained as a sudden glimpse of the underlying reality or truth. It is not only a “consolation” for the sorrow of this world, but a satisfaction, and an answer to that question, “Is it true?” The answer to this question that I gave at first was (quite rightly): “If you have built your little world well, yes: it is true in that world.” That is enough for the artist (or the artist part of the artist). But in the “Eucatastrophe” we see in a brief vision that the answer may be greater—it may be a far-off gleam or echo of evangelium in the real world. The use of this word gives a hint of my epilogue. It is a serious and dangerous matter. It is presumptuous of me to touch upon such a theme; but if by grace what I say has in any respect any validity, it is, of course, only one facet of a truth incalculably rich: finite only because the capacity of Man for whom this was done is finite.

I would venture to say that approaching the Christian Story from this direction, it has long been my feeling (a joyous feeling) that God redeemed the corrupt making-creatures, men, in a way fitting to this aspect, as to others, of their strange nature. The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels—peculiarly artistic, beautiful, and moving: “mythical” in their perfect, self-contained significance; and among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable Eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the Eucatastrophe of Man's history. The Resurrection is the Eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy. It has pre-eminently the “inner consistency of reality.” There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true, and none which so many skeptical men have accepted as true on its own merits. For the Art of it has the supremely convincing tone of Primary Art, that is, of Creation. To reject it leads either to sadness or to wrath.

It is not difficult to imagine the peculiar excitement and joy that one would feel, if any specially beautiful fairy-story were found to be “primarily” true, its narrative to be history, without thereby necessarily losing the mythical or allegorical significance that it had possessed. It is not difficult, for one is not called upon to try and conceive anything of a quality unknown. The joy would have exactly the same quality, if not the same degree, as the joy which the “turn” in a fairy-story gives: such joy has the very taste of primary truth. (Otherwise its name would not be joy.) It looks forward (or backward: the direction in this regard is unimportant) to the Great Eucatastrophe. The Christian joy, the Gloria, is of the same kind; but it is preeminently (infinitely, if our capacity were not finite) high and joyous. But this story is supreme; and it is true. Art has been verified. God is the Lord, of angels, and of men—and of elves. Legend and History have met and fused.

But in God's kingdom the presence of the greatest does not depress the small. Redeemed Man is still man. Story, fantasy, still go on, and should go on. The Evangelium has not abrogated legends; it has hallowed them, especially the “happy ending.” The Christian has still to work, with mind as well as body, to suffer, hope, and die; but he may now perceive that all his bents and faculties have a purpose, which can be redeemed. So great is the bounty with which he has been treated that he may now, perhaps, fairly dare to guess that in Fantasy he may actually assist in the effoliation and multiple enrichment of creation. All tales may come true; and yet, at the last, redeemed, they may be as like and as unlike the forms that we give them as Man, finally redeemed, will be like and unlike the fallen that we know.

So, yeah… go read On Fairy Stories.

It’s (almost) Hobbit Day after all. Celebrate by cozying up in a comfy chair, perhaps with a cup of tea if you like, and reading an essay that could perhaps change your life in the way it did mine.

That’s all I’ve got for today! Feel free to let me know any of your thoughts on On Fairy Stories or any of Tolkien’s other works down below. Have a lesser known favorite? I’d love to hear it, the man’s profound.

In any case, have a lovely (almost) Hobbit Day everyone and I’ll see you next time!

Prayers as always :)

I’ve long stated to anyone who would listen that “On Fairy Stories” is my favorite piece of writing in the English language. It really can change your life if you let it!